The University Library’s rare books collection is housed in a specialised cube on the 7th floor of the Library. It includes a wide variety of titles published between 1473 and 2002, with strengths in the 18th and early 20th centuries. One of its highlights include our Holy Trinity Collection which researcher Joan Lee, has been analysing for the past several years. Joan writes of the collection in this latest blog post.

When Eleanor Crowle, wife of the Mayor of Hull, donated volumes to Holy Trinity Church in 1665, she inadvertently formed the basis of a library of devotional literature which survived until 1906, amassing more than 800 volumes, rare and valuable Bibles, dictionaries, commentaries and sermons, together with the inevitable dross. The residue of this collection is what is now in the Rare Book collection in the Brynmor Jones library. In a survey of 1906 Holy Trinity was considered to be so unstable as to threaten collapse of the tower, and the entire library was offered for sale to finance the renovation. The most valuable, or attractive, volumes left Hull without trace, the remainder passed into the care of the Museum and, subsequently, the University.

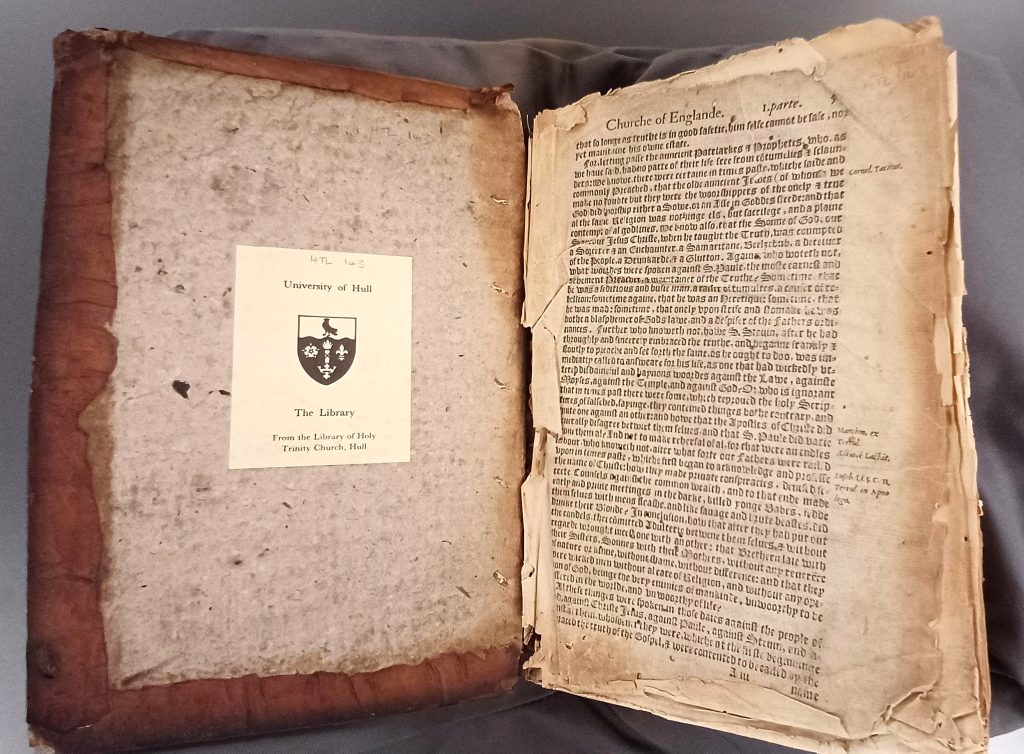

During the years of WW2, the books were sent ‘for safekeeping’ to churches in the East Riding, and on their return were in appalling condition; instead of being housed in a dry, airy tower they had been consigned to the crypts, in dark, wet infestation. Some have since been repaired and rebound, others, though stabilised, remain in a poor state. Many were donations, and it was the examination of these that was required as part of the Heritage Project, to establish the original owner and benefactor where possible. As a retired library person, and volunteer at Hull Minster, in December 2019 I was asked to undertake this.

But what a treasure trove this is! Of the remaining 471 volumes, we are able to identify the former owners, or donors, with 80 different names. Many are significant people in our city’s history, and it is an indication of their disposable wealth and status that they could afford to make such gifts. The content traces the changes in religious faith in Hull as wealth, culture and society affected Christian observance, with the dawn of the Age of Reason, and the overseas influence through being a sea city. The collection is an eclectic, indiscriminate mix; Cook’s Voyage to the South Seas shares shelf space with Fulke’s defence of the translation of The Bible, an early volume retains much of the original wooden boards while another rejoices in a binding from a fly embossing press, Hebrew texts of the psalms nestle with John Scott’s moralistic Victorian sermons.

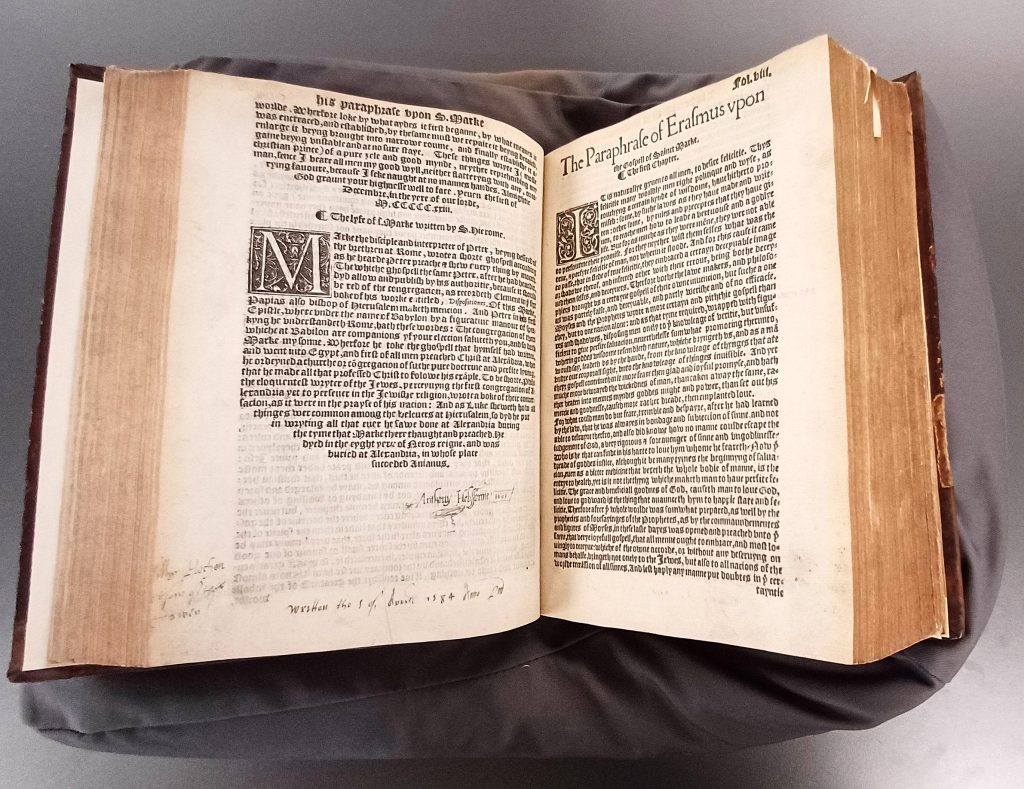

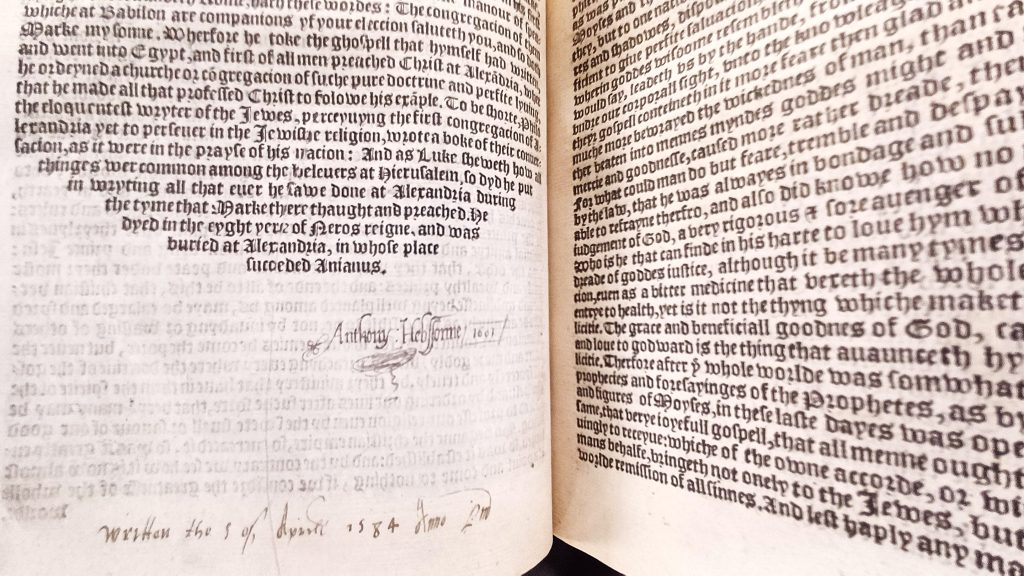

The inscriptions range from the scrawl of the barely-literate to the flowing elegance of the cultured gentleman-antiquarian, the people of Hull over the last 400 years. Of course, many volumes would have passed through the hands of several owners, some of whom have left their mark, with signatures, dedications, drawings, marginalia and so on. In Hedon, Henry Kelds complains bitterly that the population is as full of sin “as any age that was since our Saviour Christ tyme”. Thomas Hodgson is delightfully self-deprecating, bursting into rhyming couplets detailing his own inadequacies. The Rector of Dalton-Holme’s donation is “in remembrance of books lent many years ago”. Others are quite simply puzzling. One was owned by a Protestant Frenchman who ended his life on the guillotine in 1793. Another, printed in St Petersburg, is in an entirely new language, devised specifically for a tribe of nomadic Mongols with no written language of their own. How these came to Hull is anyone’s guess. Every book tells a story, many of these tell more than one.

Following a collection over several centuries encapsulates the history of book production, changes in style and practice that have become accepted conventions, page layout, numbering, style and form can be traced as technology developed, fashions in binding, and the machinery that enabled it, and of course the presses themselves – each in itself an education.

Unquestionably, my favourite is the translation of Erasmus’s Commentaries on the Gospels. It has been beautifully repaired, restored and rebound, and though missing the title page and several leaves, the Gothic black letter type is as crisp, clear and readable as this morning’s newspaper. It has been a privilege and pleasure to be involved in this task. The volumes themselves have undoubtedly benefitted from such close examination; the leaves exposed to clean air, the binding gently eased with careful handling, being taken down, handled and read. That’s what books are for.