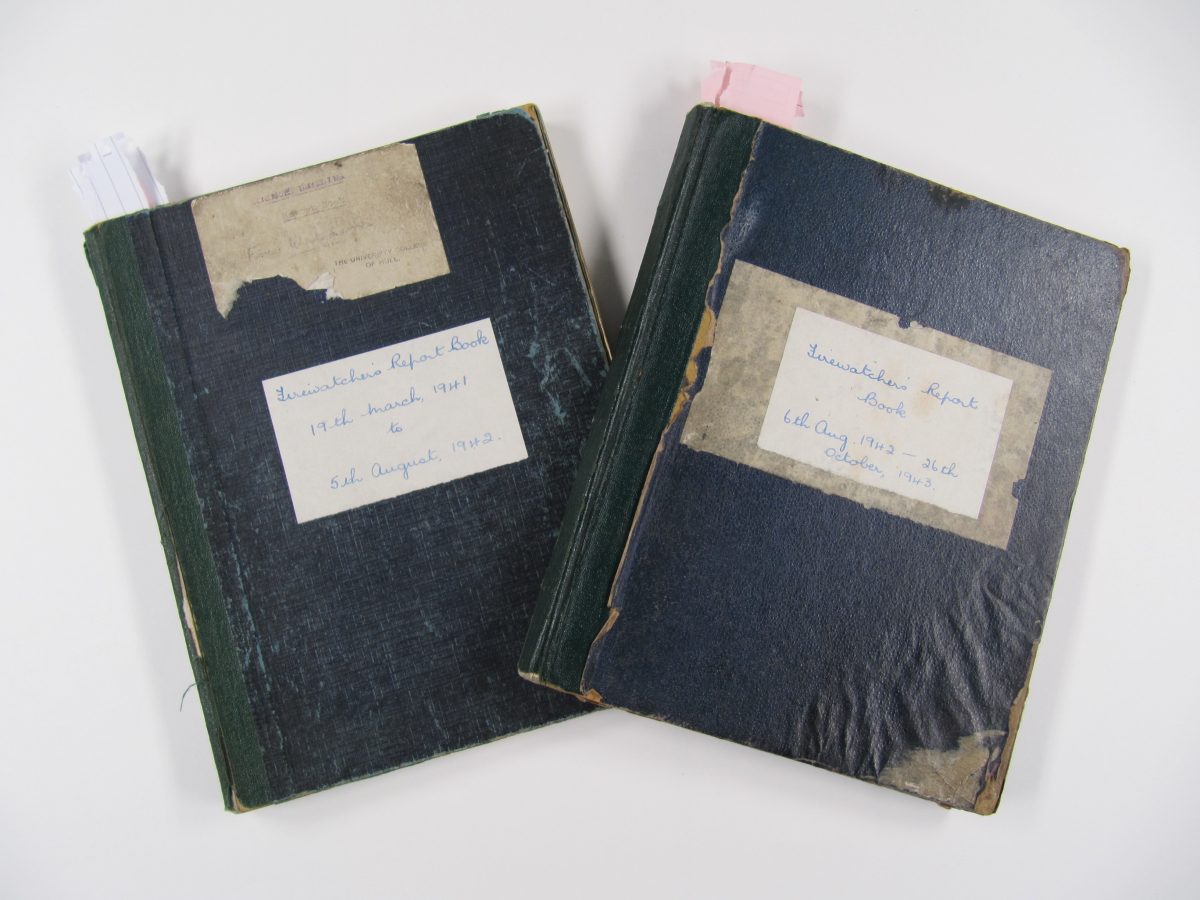

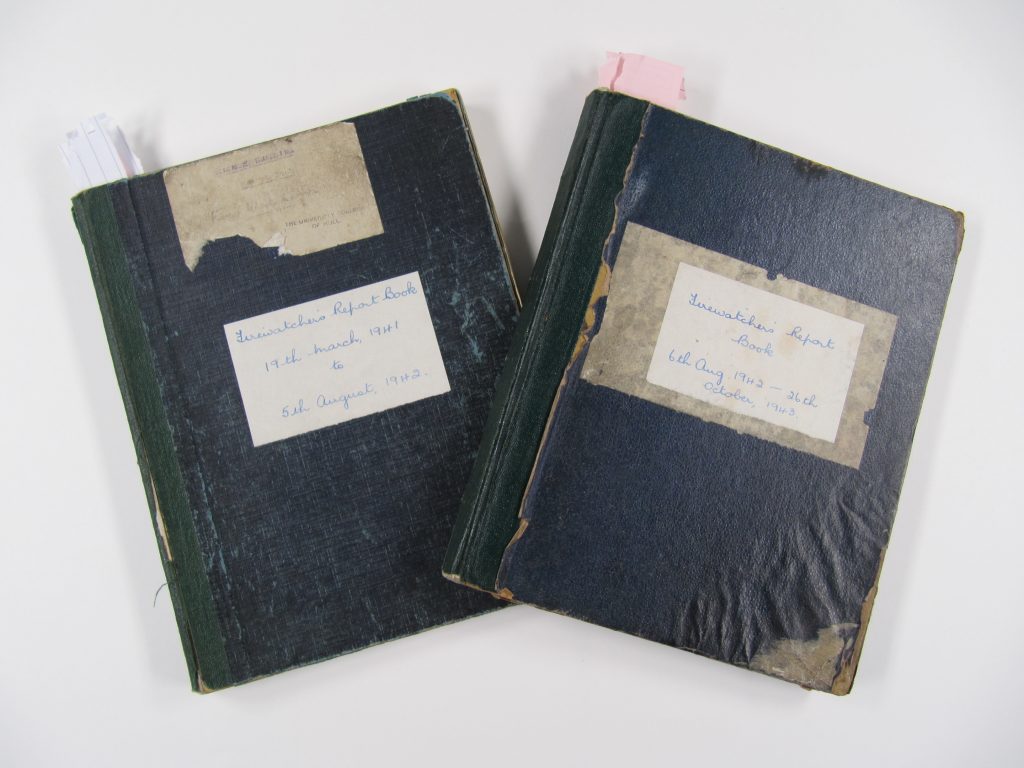

Every now and again we uncover a small collection of records at Hull University Archives that really bring life to years gone by. One such discovery was made in 2019 whilst staff were preparing an exhibition and source guide on Second World War records. Amongst the early records created by the University of Hull, we found a series of Second World War firewatchers’ report books with associated papers.

These records give us a fascinating glimpse into some of the air raid precautions that were taken by the University.

A fire-watching scheme

The University initiated a scheme for fire-watching in February 1941. The need for such a scheme was driven by heavy bombing raids on the city. These bombing raids often caused fires to spread in areas where bombs fell.

Willing volunteers

75 staff and students signed up for the scheme in the initial months, indicating a clear enthusiasm at the University to support Civil Defence efforts. This, however, was not enough to ensure that each volunteer only worked the maximum 48 hours per month suggested by the government’s Fire Prevention (Business Premises) Order 1941. The average number of hours worked by fire-watchers at the University was 63 per month. By 1942 staff and student numbers were depleted as a result of enlistment. It was only possible to continue the fire-watching scheme because many men carried out both fire-watching and other civil defence duties. Female students stepped into the gap, undertaking fire-watching duties at the Needler Hall accommodation building.

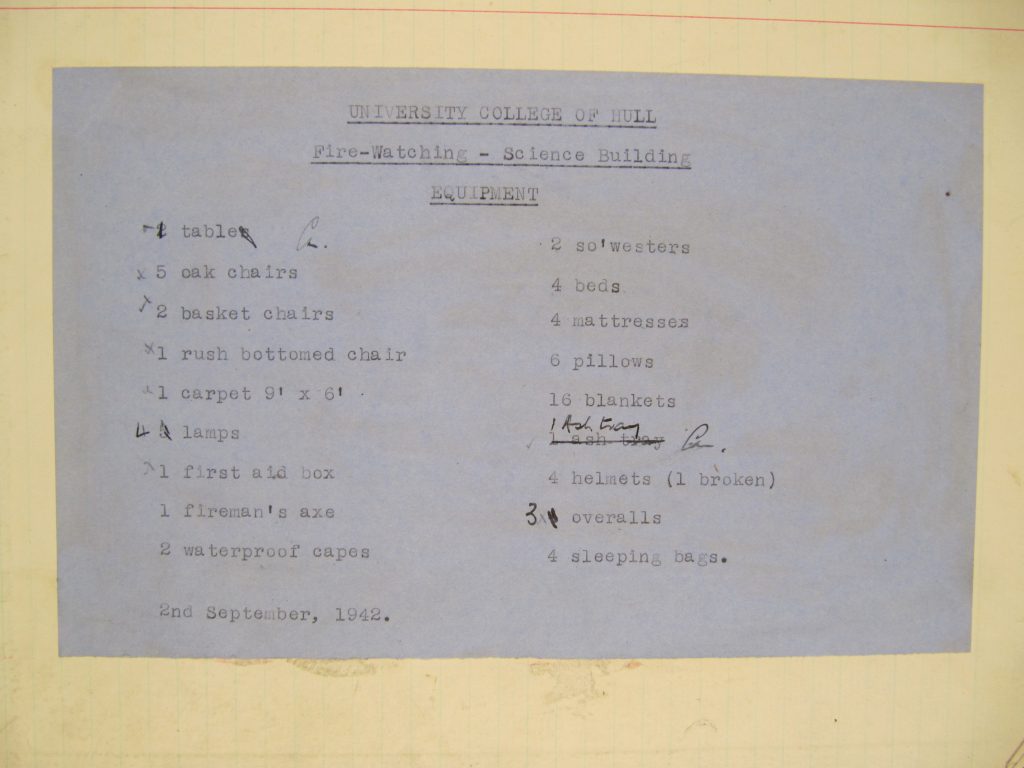

Equipment

The University provided equipment for the use of firewatchers on duty, along with instructions for what to do:

‘If a fire bomb has lodged above ground, use the rake to pull it down to the floor, then apply sand’; and ‘Dustbin lids are to be used as shields when dealing with incendiary bombs’.

Excerpt from instructions given to firewatchers by the University

Fire-watching posts

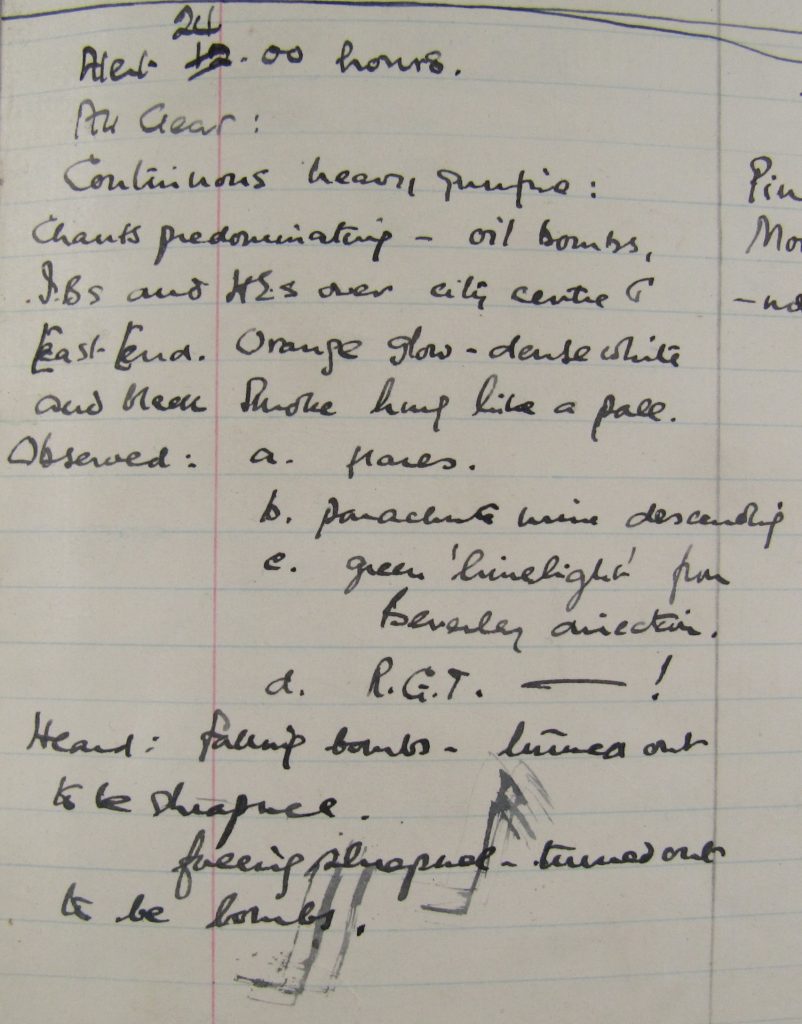

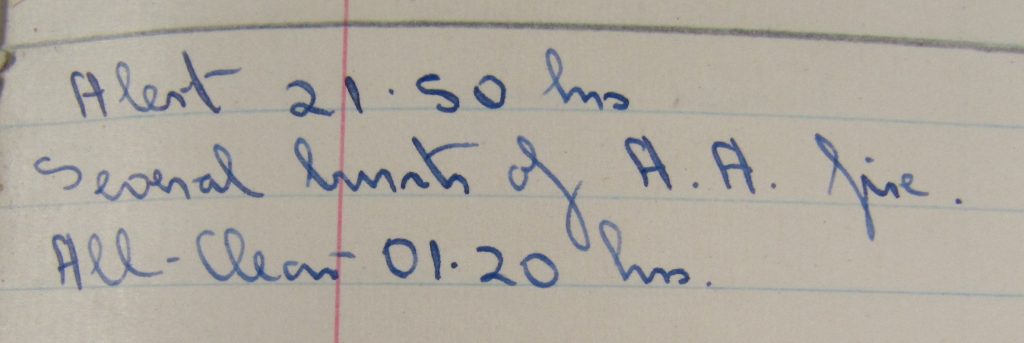

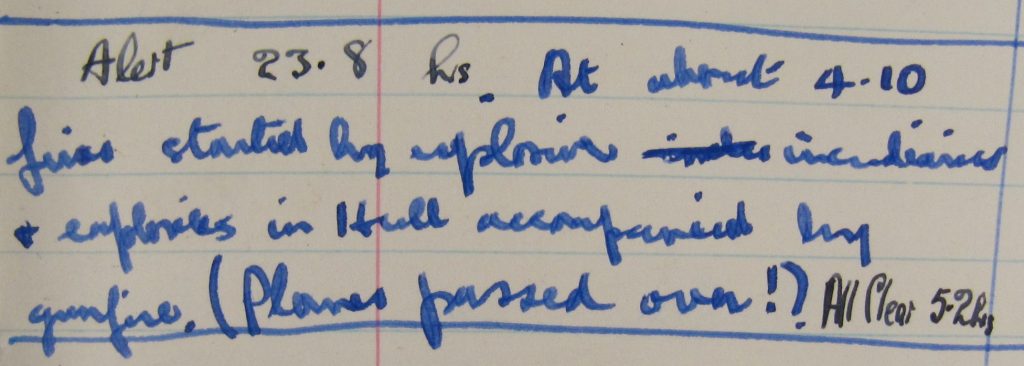

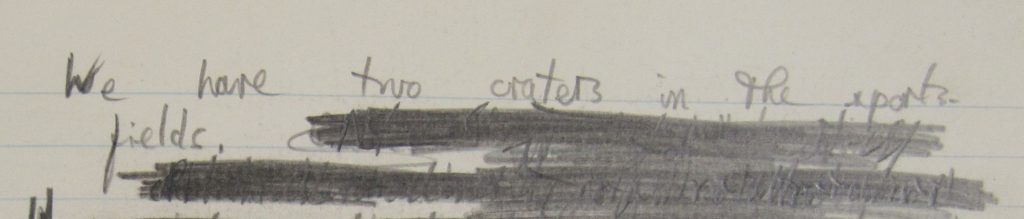

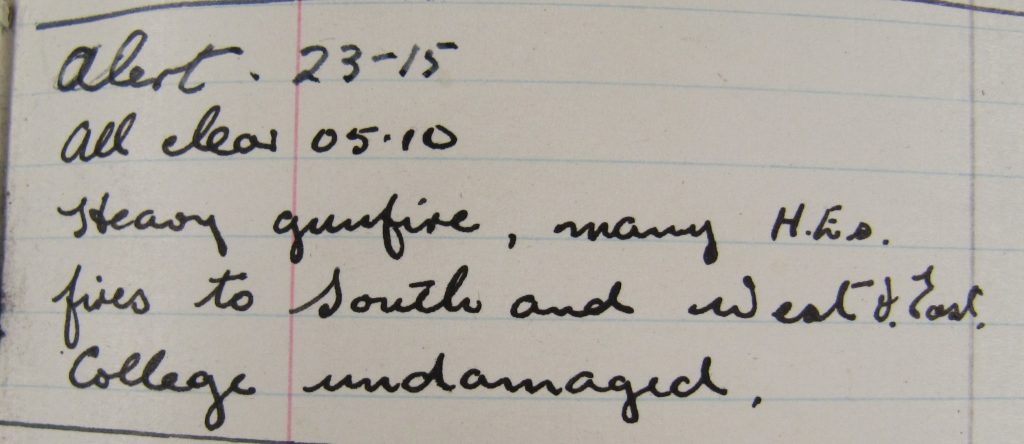

Staff established fire-watching posts on top of the Science and Arts Buildings. Fire-watching duties included raising the alarm if a fire was spotted, as well as making a record of any air raid alerts, plane sightings, anti-aircraft activity, and all clear sirens.

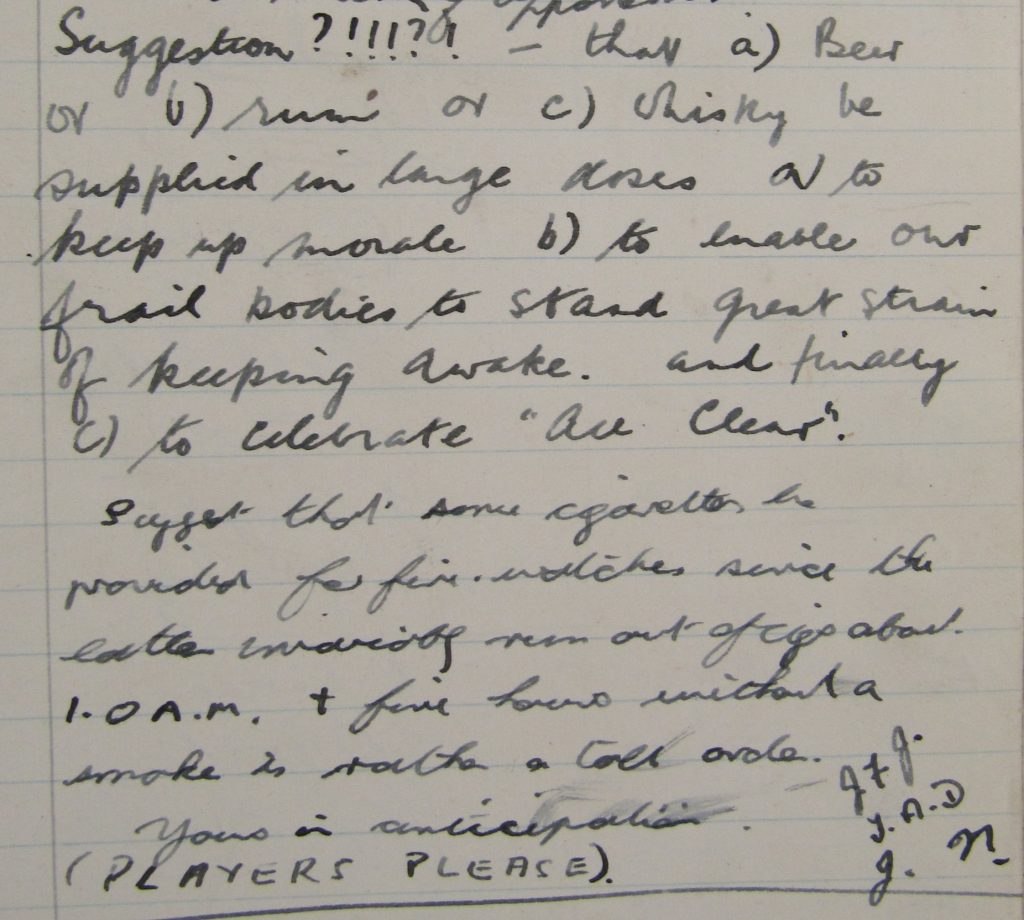

Maintaining morale

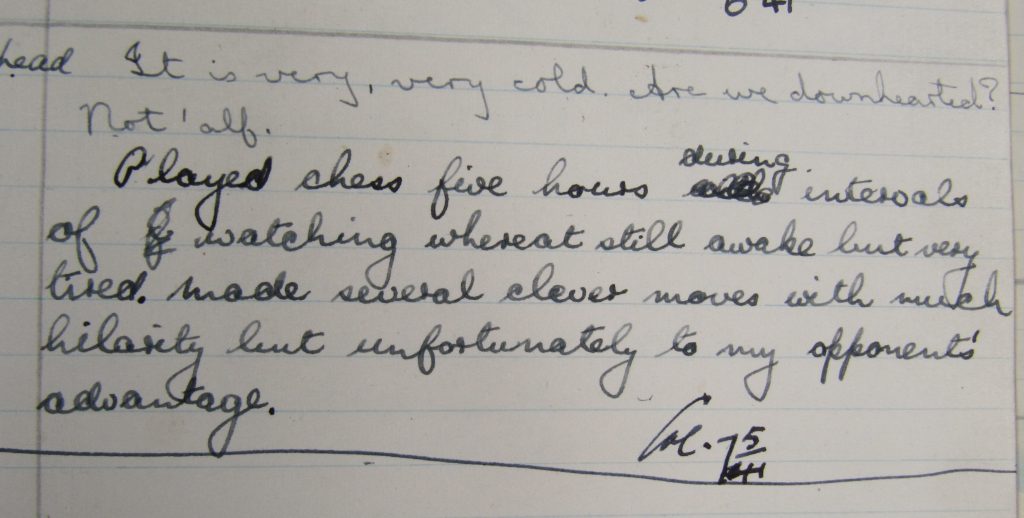

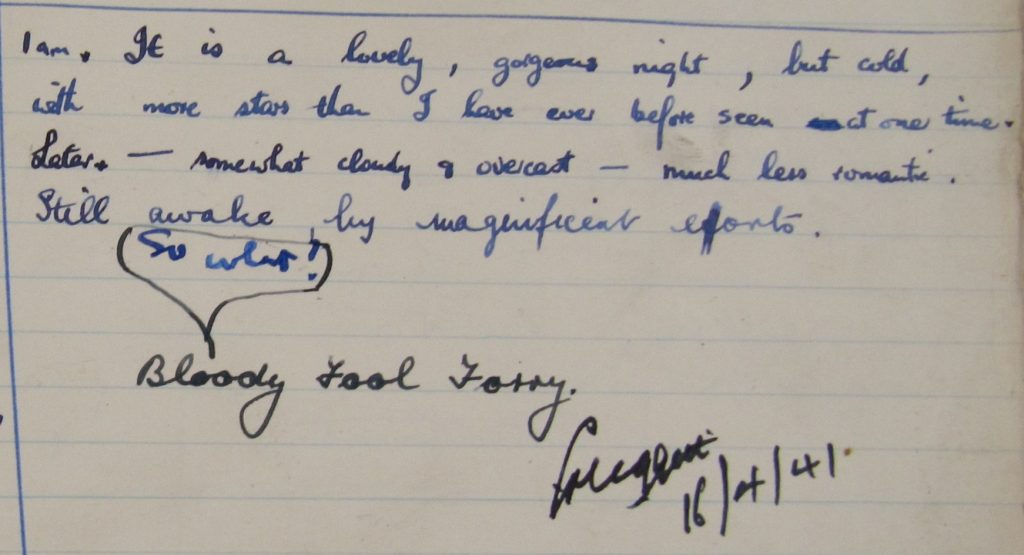

Shifts were long, lasting from 6pm to 9am the following morning. Four fire-watchers were on duty each night. The four fire-watchers were to consist of one staff member and three students. At least one individual had to be on look out at all times.

It is unclear as to whether the above suggestions were granted…probably not! To pass the time more soberly the fire-watchers played games:

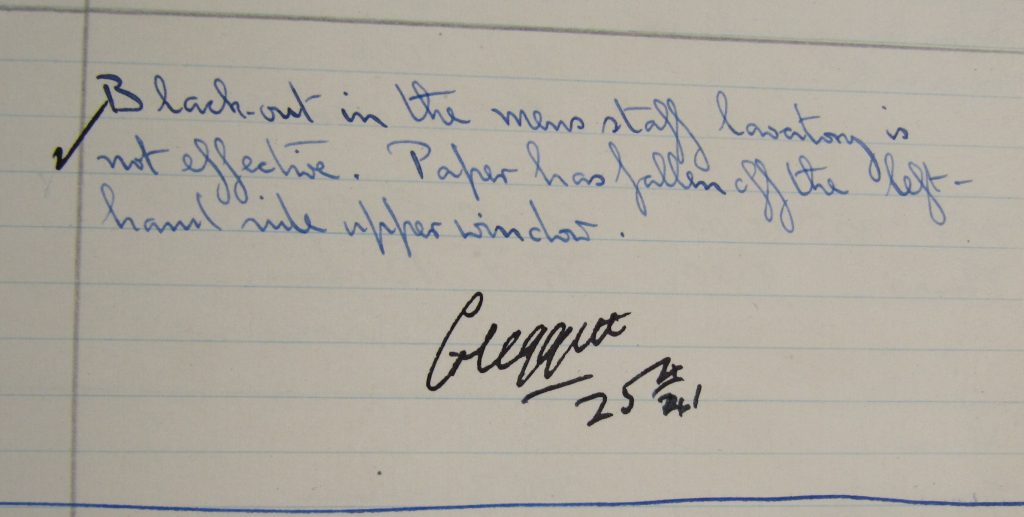

Blackout duties

In addition to their duties as fire-watchers, the volunteers also served as blackout officers. If any light could be seen emanating from windows or doors, the University buildings might become a target for enemy planes flying overhead. Blackout infractions are detailed in the fire-watchers’ report books:

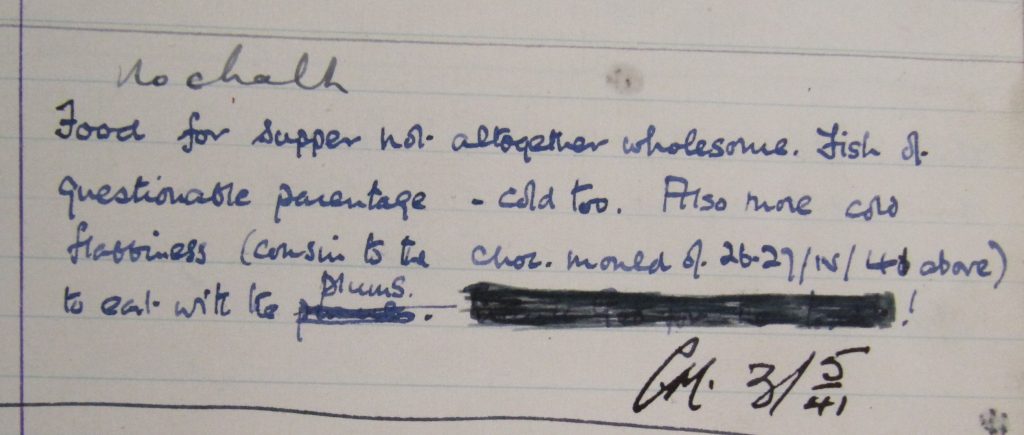

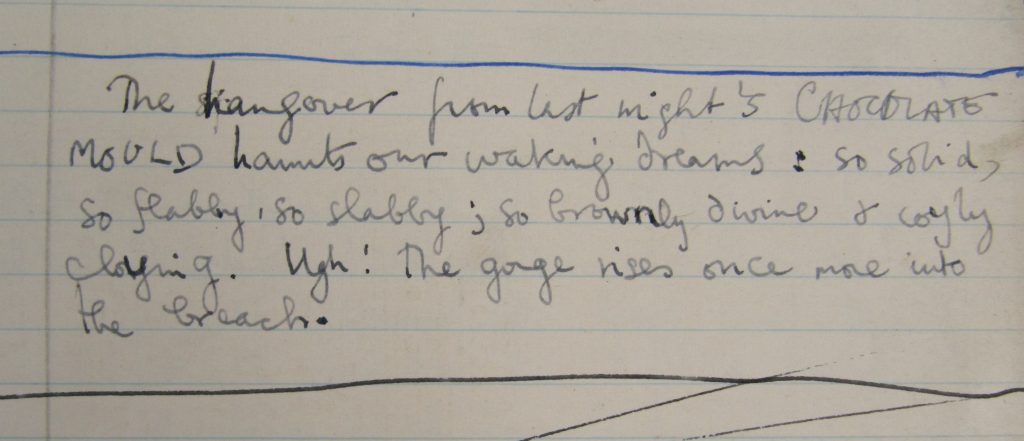

Provisions

The volunteers were provided with meals and hot drinks by the University. Comments entered into the report books show that provisions weren’t always considered ‘up to scratch’ by those on duty:

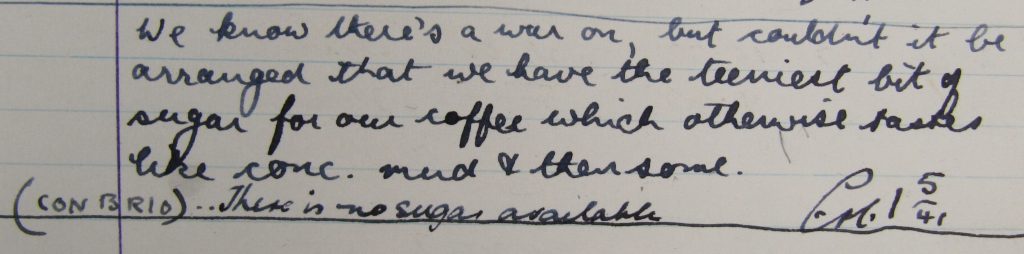

But we must remember that there was a war on and supplies were short, although this doesn’t appear to have prevented the volunteers from complaining:

Close but no cigar

Other than a few near misses and a bit of superficial damage, the report books show that the University campus escaped any major incidents during the Hull Blitz of 1941-1942.

Unbroken spirit

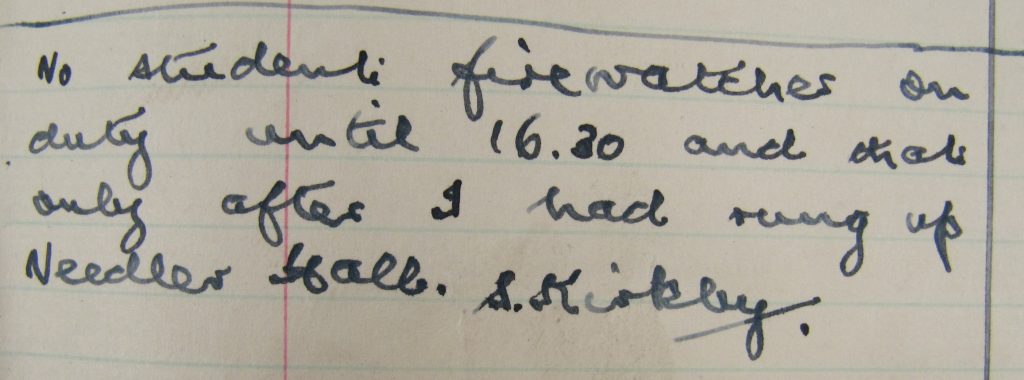

Fire-watching at the University continued throughout the war, only finishing on 24 March 1945. However, the report books show that the initial enthusiasm for volunteering had worn off by late 1942. After this time, we find various notes indicating that fire-watchers were turning up late or not at all for their registered duty. However, given the difficulties faced by fire-watchers we can perhaps understand a dip in levels of enthusiasm. Volunteers were having to contend with faulty equipment, lack of food, loss of vacation time. By 1942, the situation was no longer novel. War-weariness had set in and the initial excitement of something quite out of the ordinary had warn off. Fire-watching had become a dull task, made worse by the drudgery of having to repeat it month after month.

These books offer us a valuable opportunity to examine the experiences of those who remained behind during the Second World War. The descriptions recorded in their pages help us to understand how the city must have looked, sounded and smelled during an air raid. And the comments made by the fire-watchers give us a glimpse at their personalities.

Check out our guide, to find out more about Second World War records at Hull History Centre.