With the upcoming coronation of King Charles III, here at the University Archives we wondered what we might have hidden amongst the collections that related to coronations past. It turns out we have a small but interesting selection of material. As we might expect, there were a number of nationally produced commemorative publications and souvenir […]

Tag: archives

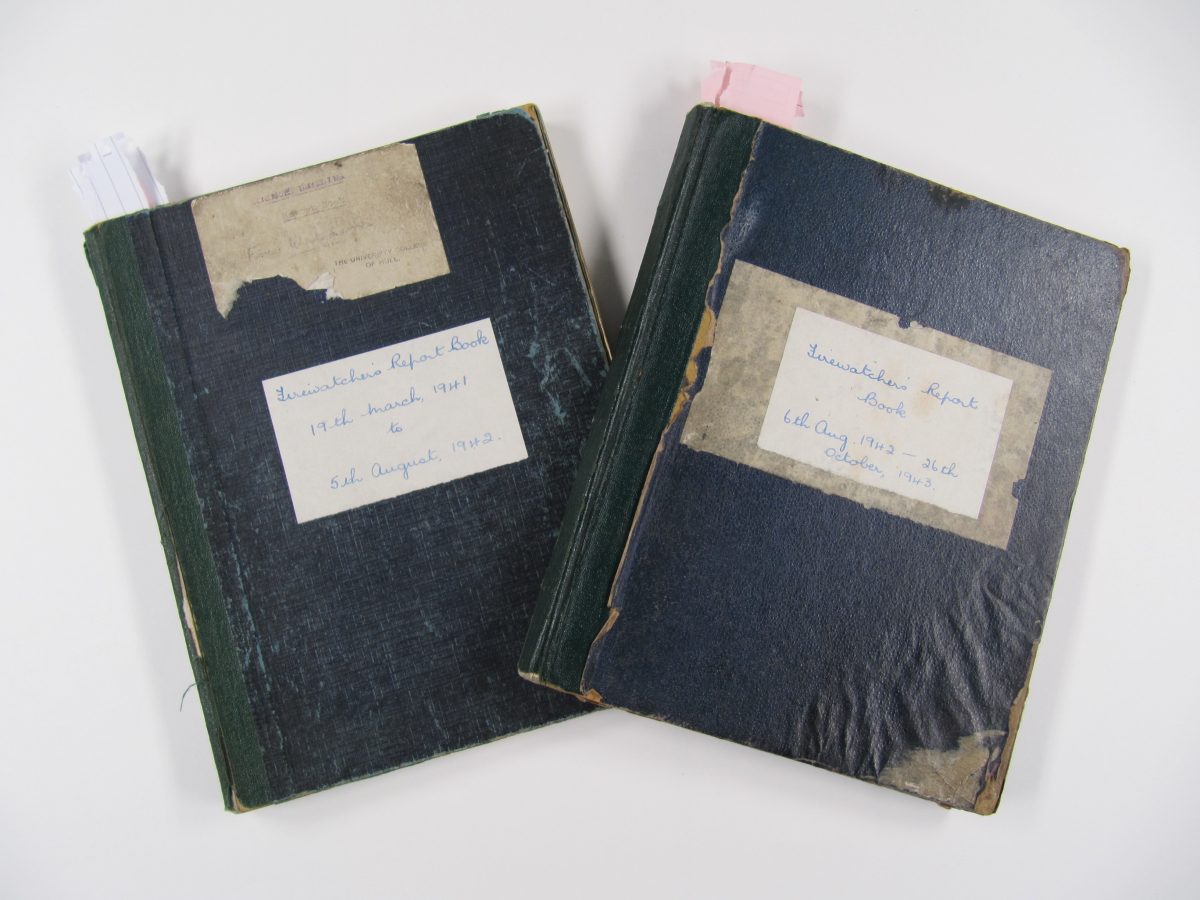

Every now and again we uncover a small collection of records at Hull University Archives that really bring life to years gone by. One such discovery was made in 2019 whilst staff were preparing an exhibition and source guide on Second World War records. Amongst the early records created by the University of Hull, we […]

Born 1908, Philippa was a writer and the daughter of the English painter, Louie Burrell. Philippa spent much of her childhood travelling the world with her mother, as Louie tried to make a living by painting portraits for wealthy individuals. Philippa made friends easily and was often a hit with her mother’s wealthy clients. She […]

Looking to be inspired for our January Hull University Archives blog, we started browsing online content for January anniversaries. It turns out there’s a huge number of food and drink related celebrations; there’s Chocolate Brownie Day on the 8th, Hot Tea Day on the 12th, Hot and Spicy Food Day on the 16th, Gourmet Coffee […]

With just a few days to go, we’re starting to get that Christmas feeling at Hull University Archives! So we’ve been looking through the collections for references to Christmases past. These are some of the things we found… Send a card To get us started, here’s a Christmas card printed by our University for the […]